✅ You’re All Set!

If you don’t see a confirmation text within the next few minutes, check your spam or blocked messages folder.

Pro tip: Add our number to your contacts so you never miss an update.

View your bonus report below!

Birthright Boomtowns: A Look At The Top 5 Resource Rich Hotspots In The USA

Dear Reader,

Jim Rickards here with what I believe could be the biggest opportunity in the history of Paradigm. I'm referring to a trillion-dollars windfall that I believe will reignite the American Dream for millions of everyday folks, virtually overnight.

In fact, if you act by the end of this month, 2026 could bring life-changing wealth.

For generations now, we've been watching the American dream keep slipping away for everyday folks. Costs have risen. Wages have fallen. Opportunity vanished. Millions were left behind believing the American Dream was dead.

But I'm here to tell you that the American dream is not dead. It was merely locked away behind decades of red tape and bad policy. It was Washington’s failure to invest in America's mineral bounty, the source of this country's riches, that has led to our nation's decay.

Our country is currently dependent on other countries – particularly adversarial China – for some of the most critical minerals and elements that power our economy.

But Washington has finally seen the writing on the wall. The federal government is now taking direct stakes in natural resources stocks to free America of its mineral dependence on other nations and to revitalize our industrial capacity.

For example, in July 2025, the U.S. Department of War announced that it would become the largest shareholder of MP Materials. This company is the operator of the only rare earth mine and processing facility in the United States.

The government followed up this acquisition on September 30, 2025, with a $2.3 billion loan to Lithium Americas in exchange for 5% of that company, and again on October 7, 2025, with a $35.6 million investment in Trilogy Metals for a 10% stake.

But there's a gigantic update coming in this story happening as I write…

Washington is setting up a $5 billion fund to invest in critical mineral projects like the ones we discussed above. A little-known federal agency is about to trigger the largest natural resource boom in the history of this country.

This will result in a massive wave of private-public investment, driving mining stocks chosen for federal investment to huge gains. We're talking about the potential to unlock the American Dream for you and your loved ones.

Old ghost towns and dying communities will return to life and prosper with new mining activity. Newer locations will be built out, creating ecosystems of jobs.

To help you understand the scope of this story, and where some of its most exciting developments could take place, I enlisted Byron King to help me gather a list of potential Birthright Boomtowns. Below, Byron will guide you through the history and riches at these sites.

But to truly understand the full stakes of this Birthright story – and how it could reinvigorate the American Dream for millions of Americans – tune in for a special summit taking place this Thursday, 1/15, at 1:00 PM ET.

During this urgent summit, I will be talking with one of the world's top geologists – a brilliant mining company CEO and investor – who will reveal the best ways to profit from America's mining reindustrialization.

Furthermore, when you join this urgent summit, you'll learn how to access a brand-new dossier called Wall Streets #1 Mining Stock. This dossier contains details on a stock that could double in the next 18 months.

So, make sure you attend the Summit on Thursday. It's one you cannot afford to miss.

See you then,

Jim Rickards

Editor, Paradigm Press

America's Top 5 Resource Rich Hotspots

Byron here.

American mining towns have a rich history of booms and busts. But while some were depleted, others still contain mineral troves.

Meanwhile, as these historic sites draw fresh attention from miners and investors, newer mining towns are also rising across the U.S.

With that in mind, let's dive into America's Top 5 Birthright Boomtowns…

Boomtown 1: Tombstone, AZ – A Tombstone Made of Silver

It’s a long way from the green hills of Wellsboro, Pennsylvania to the desert scrub of southeast Arizona, but Edward Schieffelin (1847 – 1897) was born in the former locale and became fabulously wealthy in the latter jurisdiction.

At age 17, Schieffelin headed West to seek his fortune as a prospector in newly opened territories that encompassed the Rocky Mountains.

Ed Schieffelin, prospector and Army Scout. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Later in life, Schieffelin became a scout and mapmaker with the U.S. Army. He rode horseback into unknown landscapes and kept an accurate record of wherever he went.

Eventually, the Army assigned Schieffelin to Arizona. One day, he was riding up a dry streambed in Cochise County, and looked down to see what appeared to be silver-bearing ore. He dismounted, examined the rocks, and followed other traces uphill to a wide plateau.

After completing his surveys, Schieffelin rode back to Tucson where, instead of reporting to his Army unit, he headed for the federal courthouse to file mining claims.

One of Schieffelin’s associates heard about the claims and was skeptical. He scoffed at Schieffelin and said, “Ed, the only rock of any value you’ll find out there is your tombstone.”

Schieffelin smiled and went about his affairs.

Long story short, he returned to his mining claims and uncovered massive deposits of silver ore, including a deposit containing many hundreds of millions of ounces, enough to lure significant investment from mining companies and a railway spur to a nearby depot.

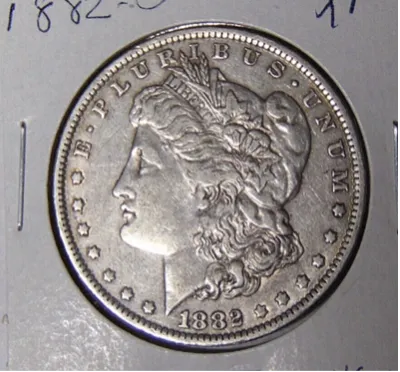

Recalling the early mockery of his claims, Schieffelin named the new mining town “Tombstone.” And from the late 1870s to early 1900s, Tombstone, Arizona was one of America’s richest silver districts, and a key supplier of metal to the U.S. Mint for use in currency like silver dollars.

A Tombstone Silver Dollar, 1882, New Orleans Mint. BWK collection.

Today, Tombstone is also iconic in American history for the story of the famous “shootout at the OK Corral,” a Wild West tale all its own. (Although, it’s worth noting that the episode is rooted in the vast wealth that miners were pulling, at the time, from the tunnels beneath the town.)

All of this was way back when, to be sure, and part of America’s rich mining history. But it’s also indicative that the U.S. contains vast riches still buried in ancient rocks from sea to sea, and all the lands between.

The Future Tombstone

Since the days of Schieffelin, Arizona has never ceased being a mining state. The same geologic forces that concentrated silver in the rocks beneath Tombstone are apparent all across the region. Arizona remains one of the most mineral-rich regions in North America.

The state hosts porphyry copper systems, other polymetallic deposits of copper-silver-gold, and related mineralized belts that stretch for hundreds of miles beneath desert scrub and ranchland.

The question for 2026 and beyond is not whether Arizona will host another mining boom – it is what form that boom will take and where it might surface.

If history rhymes, one of America’s next mining booms is likely to emerge in the southeastern part of the Copper State. Cochise, Pima, and Graham counties sit atop proven mineral systems, supported by road and rail access, power lines, legacy infrastructure, and a workforce accustomed to mining’s rhythms.

Many mineral deposits in this region were identified decades ago but set aside when economics failed to justify development. Of course, those calculations were made under very different price structures and different assumptions about development.

Today, much has changed for U.S. mining. Among other metals besides silver, copper has taken on a strategic character. Electrification, grid expansion, data centers, electric vehicles, and defense systems all draw from the same finite supply chain. That convergence creates conditions under which large, long-life deposits, once considered marginal, can again command attention and capital.

A new mining boom could occur near an existing but underdeveloped district, perhaps near long-established towns such as Bisbee, Willcox, or the broad corridor east of Tucson. But any modern version of an Arizona boomtown would bear little resemblance to Tombstone of old.

Instead, new mineral development would unfold methodically, driven by institutional capital, long permitting timelines, and decades-long mine plans. The result would be quieter, slower, and unfold at a far more definable and economic scale.

Boomtown 2: Butte, Montana – The Richest Hill on Earth

In the mid-1860s, as the Civil War raged back East, many Americans headed West both to avoid the fighting and to seek their fortunes. Some of these travelers passed through a place then-called Summit Valley in western Montana, an area that straddles the Continental Divide.

This spot of earth was crisscrossed by streams and creeks that drained nearby highlands, and in no time, sharp-eyed prospectors saw valuable minerals in the drainage beds. The locale quickly became a small-scale mining district for gold and silver.

Unfortunately, gold and silver ores were commonly associated with copper minerals as well, and this was a problem because metallurgy at the time could only separate those metals at great expense.

By the late 1870s, however, chemists had developed processes to isolate copper. As fate would have it, this coincided with another major development in America: The country began to string telegraph wires at continental scale. Then, in the 1880s, the country began to string wires to conduct electricity. Both of these efforts required near-endless miles of copper wire.

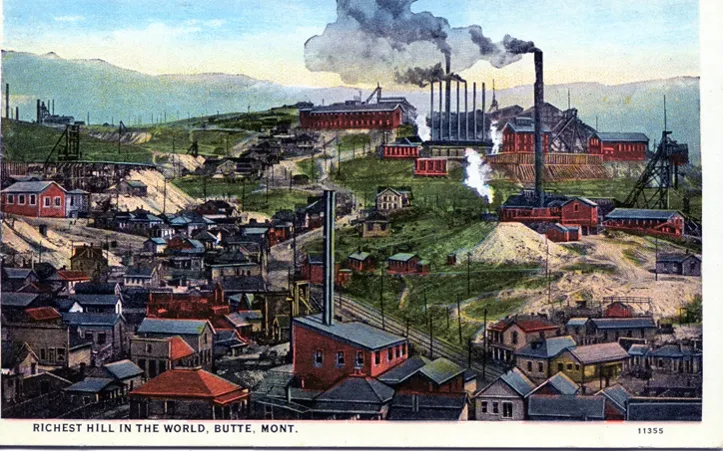

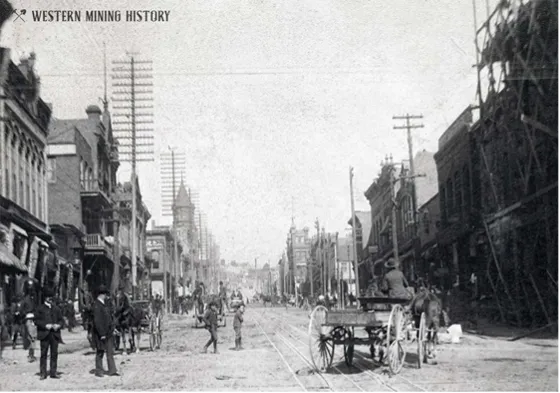

Postcard, Butte, Montana 1880s. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Butte was established as a mining town adjacent to a literal mountain of copper ore, associated with an ancient granite intrusion. Locals called it “The Richest Hill on Earth.”

Over time, Butte would have over 10,000 miles of mining tunnels dug beneath it, along with several massive open pits, all in pursuit of copper, with associated gold, silver and other metals like molybdenum, tellurium and more.

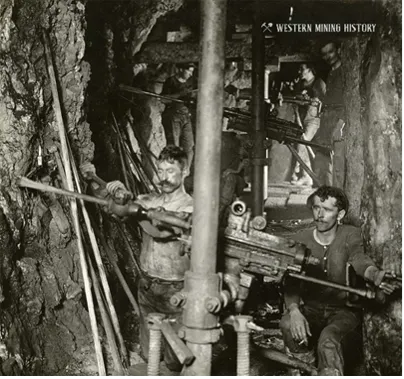

Butte in 1900; drillers working 1,900 feet underground. Courtesy WesternMiningHistory.com.

Butte itself was now among the richest towns in the U.S., with per capita incomes easily surpassing the numbers from established cities like New York, Pittsburgh, Chicago or San Francisco.

Main Street of Butte in 1892. Courtesy WesternMiningHistory.com.

Butte’s days as a copper mining powerhouse lasted through much of the 20th century, into the 1970s, with the last major mine – the Berkeley Pit – closing in 1982.

The copper mines didn’t close for lack of copper ore, nor gold, silver and much more. Far from it. No, the mines closed because of low prices for metals and associated high costs of production in the U.S. considering the price of energy, plus labor, regulations in general and, especially, environmental regulations.

This brings us to the current times, with strong metal prices and a strategic need for the U.S. to secure assured supplies of critical materials like copper and much else. And the fact is that the mountains and rocks around Butte, and all across western Montana, are rich and prospective for valuable minerals. It’s a future story waiting to be written.

To the northwest of Butte is the so-called “Silver Triangle” of northern Idaho, stretching southward in that state and spilling east into Montana. And east and southeast of Butte are numerous other known locales for copper, gold, silver, platinum, nickel and much more, continuing down into the Stillwater Mining District.

Looking ahead, it’s no stretch to predict that western Montana – if not Butte itself – will again become the hub of a major mining boom.

Boomtown 3: Midland, Texas – A Town Built on the Second Well

Autry Stephens was born on March 8, 1938, in De Leon, Texas, the fourth of five children on a small peanut and watermelon farm. Young Stephens learned early that nothing worth having comes without sweat, sacrifice, and endurance.

That landscape of hard work prepared him for another unforgiving profession: oil and gas exploration and production (E&P). Farming and drilling share much in common as careers. Both are capital-intensive, cyclical, and fraught with risk.

Stephens began his professional journey after studying petroleum engineering at the University of Texas at Austin. In the 1960s, he worked for Humble Oil and Refining and then for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers as a pipeline fuel officer. By the late 1970s, he was in Midland, Texas, working as a reservoir engineer at a local bank.

But the bank’s structure did not satisfy his ambition; he wanted to drill wells.

So, in 1979, he took a leap that would define his life. Armed with savings and a small parcel of leased land, he drilled his first well in the Spraberry Trend, a major oil field encompassing Midland in the Permian Basin.

From that first well emerged the company that would become Endeavor Energy Resources. Over the next four decades, Stephens grew his sole proprietorship into one of the largest privately held oil and gas producers in the United States, amassing hundreds of thousands of acres and countless producing wells across the oil-rich Permian Basin.

By the early 2020s, Endeavor’s Midland Basin operations produced hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil equivalent per day, and the company stood among the most formidable independent operators in the hottest oil patch on the planet.

For years, Stephens was resolute that Endeavor would never be sold. Peers recall him rebuffing offers from supermajors, investors, and energy giants looking to scoop up his assets.

But in 2023, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. Stephens decided to settle Endeavor’s destiny on his own terms rather than leave its future to estate decisions after his passing in 2024.

In February 2024, at age 85, he agreed to sell Endeavor to Midland neighbor Diamondback Energy in a transformative transaction valued at $26 billion. Under the merger agreement, Diamondback paid $8 billion in cash alongside 117.3 million shares of common stock to Endeavor’s equity holders.

The deal ranks among the largest in the U.S. oil and gas sector. It consolidated two Midland-based powerhouses into a premier Permian operator with enhanced scale, inventory, and operational depth.

Midland in the Next Cycle

Midland knows boom and bust like few places on earth. It has been a boomtown many times over – first during early Permian discoveries, then with the shale revolution, and again as the region emerged as the core of U.S. hydrocarbon production.

With Endeavor now part of Diamondback’s larger platform, Midland’s role in America’s energy future is once again growing.

Oil prices and rig counts are cyclical, but Midland’s geological advantage is not. It is rooted in the deep stacked reservoirs that underlie West Texas. It also has irreplaceable infrastructure, including pipelines, processing facilities, skilled labor pools, along with decades worth of local industry expertise.

The rigs may slow on occasion, but the energy locked in Midland’s rocks does not disappear. When prices rise and operators expand drilling activity, Midland will feel the impact early. Rig counts will climb, crews will return, and the town will expand outward with jobs, housing demand, and renewed economic activity.

Boomtown 4: Beatty, Nevada – A Small Town Ready For Gold Boomtown Growth

Frank “Shorty” Harris, like any good prospector, never went anywhere without his pick.

“A man never knows just when he is going to locate pay ore,” he later recalled. Shorty didn’t expect to find it that morning. But there, near a ledge of rock streaked with copper stains, he swung his pick, and history was made.

The rock Shorty found was like nothing they’d ever seen. It was green as turquoise, flecked with thick veins of gold. It reminded Shorty and his partner of the back of a frog.

Just like that, "Bullfrog Mine" was born.

The Bullfrog Gold Rush

The news of the gold spread like wildfire. When Shorty returned a week later, over a thousand men had already swarmed the hills, scrambling to stake claims. Some had tents, but most slept under the stars.

Soon, the ragtag mining camp became the roaring boomtown Rhyolite, Nevada. Wagons full of lumber rolled in. Businesses sprang up overnight. Wild speculation sent property prices soaring. Rhyolite had electric lights, a stock exchange, and even its own opera house. Some believed it would rival San Francisco.

At first, Shorty sat tight, watching their claim’s value climb. The big-money men started sniffing around. Industrialist Charles Schwab bought into the district in 1906. But before that, prospectors and gamblers were making offers left and right. Shorty, always fond of a good drink, was wined and dined by slick businessmen eager to separate him from his claim.

Then, after a six-day bender, enabled by whiskey from an acquaintance named Bryan, he woke up to bad news. “When I came to, Bryan showed me a bill of sale for the Bullfrog,” Shorty recalled bitterly. “The price was only $25,000.” His partner, Ed Cross, was wiser. He stayed sober and sold his share for $125,000 – five times what Shorty got.

The Rise and Fall of Rhyolite

Rhyolite was a mining camp built on gold fever and stock speculation. When the town's big mines ran into trouble, the bottom fell out. The ore turned out to be harder to process than expected, and as a result, investors got cold feet. The banks closed, the railroad shut down, and by 1911, Rhyolite was a ghost town.

By the time Shorty told his story in 1930, Rhyolite’s grand stone buildings stood empty, the desert reclaiming them, with jackrabbits and coyotes playing hide and seek among the ruins.

Shorty never stopped believing in the hills where he struck it rich. “There’s plenty of gold in those mountains yet,” he insisted. “If the right people ever got hold of Rhyolite, they’d make a killing. But they’d have to be real hard-rock miners.”

Shorty’s story about the Bullfrog Gold Rush and the boom and bust town of Rhyolite was published in October 1930.

Today, modern mining companies are once again poking around the Bullfrog Hills, testing the ground where Shorty swung his pick.

And it turns out Shorty was right: One of the world’s top gold mining companies is now developing a giant gold discovery about 10 miles east of his famous discovery.

The Gold Never Left

The Bullfrog district did not die because the gold ran out. It faded because the technology, capital discipline, and processing methods of the time could not unlock what lay beneath the surface at a profit. The rocks defeated the financiers long before they defeated the miners.

That distinction matters.

Today, modern mining companies are once again drilling, sampling, and modeling the same geology Shorty claimed. Advances in metallurgy, processing, and project scale have reopened districts once written off as marginal.

And when real mining returns to a district, it does not stop at the pit wall.

The question is no longer whether the Bullfrog Hills contain gold. The question is where the human activity that follows might concentrate.

If history rhymes, it will not be Rhyolite. It will be Beatty.

Why Beatty Matters

Beatty, Nevada, sits just east of Rhyolite, close enough to feel its shadow but far enough to have survived its collapse. Where Rhyolite burned brightly and disappeared, Beatty endured. It became the place people passed through rather than the place they bet everything on.

That is why it matters now. Beatty already has what modern mining needs: road access, proximity to prospective ground, basic services, and a population accustomed to living where cycles come and go. It is not a museum of the past. It is a foothold.

If a large gold operation takes shape in the Bullfrog Hills, Beatty is the logical place where housing, services, contractors, and workers would congregate.

Boomtown 5: Denver, CO – The City on the Edge of Forever

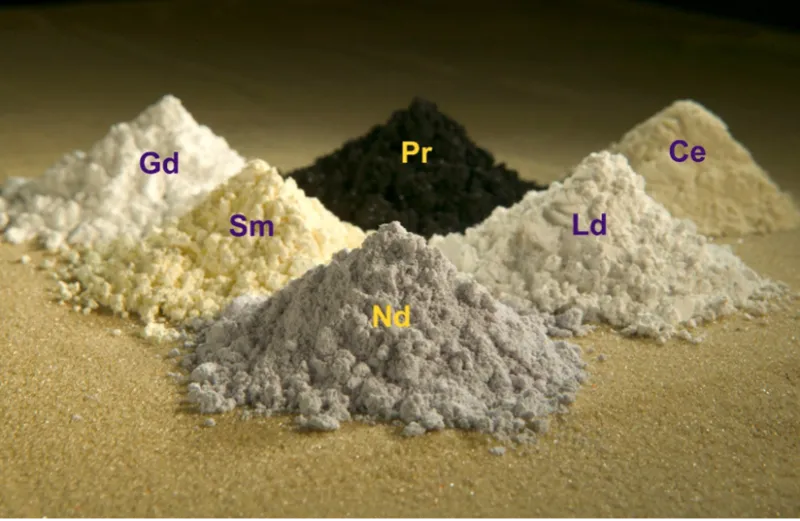

Human dependence on rare earth elements is a relatively new phenomenon.

For most of human history, people worked with elements like copper, tin, zinc, lead, silver, gold and eventually iron. Heck, even aluminum didn’t become a common metal until the mid-20th century.

But lately, much of the world’s tech relies on REEs. Your car, refrigerator, microwave oven, television, smart phone, the screen on which you are reading this… The airplanes above, the submarines below the sea, satellites in orbit…… it all has REEs within.

In essence, if we have no REES, then much of modern life as we know it craters.

REEs are elements with particular physical and chemical properties controlled by their respective electron structures. These electron structures control properties such as electronic suitability, magnetism, phosphorescence and more.

Various rare earth elements. Courtesy U.S. Geological Survey.

China controls about 90% of global refining for REEs, and has begun to squeeze the West on the matter. The U.S. is currently in a high-speed program – call it a New Manhattan Project – to develop domestic capabilities to produce REE ores and refine them into materials that industry can use.

As things stand, the U.S. is running on a very short timetable for REEs, while industry scrambles for supply and empties out warehouses and stockpiles.

So, where are America’s REE deposits?

REEs are actually all over the place. The catch is that, typically, REEs are found in low uneconomic concentrations.

In some instances, though, one finds higher concentrations of REE. These range from humble coal ash and even coal seams, to phosphate quarries, mineral sand deposits, and hard-rock deposits like out in, say, California, West Texas, Wyoming or Alaska.

The true trick is refining raw materials or feedstocks to extract REEs, which makes for exotic chemistry and engineering. Indeed, China has spent about 40+ years focusing its education system and industry on developing REE techniques, and sad to say that the U.S. lags far behind… but the good news is that the country is catching up.

Here in the U.S., you’ll find companies and places where REE extraction is being built out at near breakneck speed. Sites include South Carolina, Florida, Louisiana, Texas, Colorado, Utah, California and more.

They range in size from small caps to multi-billion-dollar players. Some will succeed; some might not. And it’s important to understand who’s who in all of this…

Looking ahead, it’s no stretch to predict that several locales in the U.S. will become REE hubs as the respective buildouts proceed.

But if we were to name one location that stands out to us…

It would be Denver, CO.

Why Denver? The city has numerous companies resident there for their headquarters, including Energy Fuels. It also has lots of research and developments based there, such as Hazen Labs. Furthermore, Denver is generally considered the mining capital of the Rockies (ahead of Salt Lake City). To top it off, it has the Colorado School of Mines, which has one of the ONLY strong REE programs of any university in the U.S.

The New American Dream Starts Here…

Here in America, the raw ore deposits and feedstocks are out there, and development is proceeding apace based on opportunity, necessity, exploration, research, development, preparation, and of course big money flowing into it all.

In other words, geology will rise to supply demand, and American research, development and applied technology will come through. It’ll be quite a ride, with tones of new mineral and material opportunities popping up across America.

For now, that's it for this free bonus report.

Remember to watch the special broadcast taking place this Thursday at 1:00 PM ET, when one of the world's greatest geologists will reveal the best ways to profit from Washington's new $5 billion fund to invest in critical mineral projects.

You'll also get the free Wall Streets #1 Mining Stock report for attending.

Thank you for reading, and hope to see you at the summit Thursday!

Best,

Byron King

For Paradigm Press